What is Genericide, and why is it so bad and how marketing can help in preventing it.

You’d think a brand would love it if people used their brand name as a word describing the whole category it belongs to. Like when you ask someone to hand you a Kleenex when the tissue box near the person is not even a Kleenex brand. Or for the brand Google to see its brand name as a verb with the other fancy verbs in the English dictionary. I thought it was cool, I thought this reflected unprecedented popularity and success of that brand in its category. However, while you and I call it cool, brands call it certain death.

Genericide is what’s it called, and it’s defined in the Oxford Dictionary as “The process by which a brand name loses its distinctive identity as a result of being used to refer to any product or service of its kind.” Shifting its position from “it’s a dominant brand in that category” to “it IS the category.” A brand’s name is not just a name, it is its identity and built up trust. Elizabeth Ward, a trademark lawyer, says “You have to see it in context of how much they spend on advertising… Once it (the brand) becomes just a word, it erodes the value of that brand.” (Duffy, 2003).

Brands spend big money making that name recognizable to the masses. Sometimes that name becomes too big, too recognizable that it gobbles up the whole category to which it belongs. A big brand that became a category no longer poses an option in the consumers’ minds. Quality, affordability, innovation any sort of association that the brand spends so much time and money on creating will be gone (Marsden, 2011). The way language develops is to blame, we instinctively pluralize a brand name like Oreos, or use it as a verb like Photoshop (Marsden, 2011). This damages the brand because over time it starts to blur, we will no longer remember its origin. Oreo will mean any dark cookies, and Photoshop can be said when using any photo editing program.

An everyday word that you’ve long been using could be a dead brand and you don’t even realize it. An escalator used to be a brand, due to the company’s own misuse of its brand in its advertising, the company lost the trademark in 1950. Because in their ads the first letter of the word “escalator” was not capitalized, the same way as ‘elevator” which is an actual generic word. So in that regard, escalator is typed as a generic word and so it is perceived as such (Marsden, 2011).

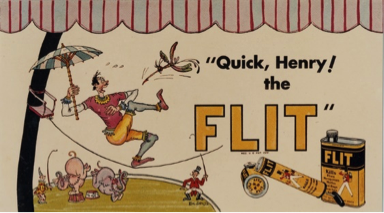

When a mosquito makes its life’s purpose to bother you, tired of swatting it, you go with an intent to kill, looking for a flit. In the GCC consumer’s mind “Flit” is a synonym to insecticide, but they don’t go looking for Flit, they’re looking for a flit. When you look up pictures of Flit, the results will show Pif Paf or Raid, the most known “flits” here in the Middle East. Those two brands dominate the search results. Flit became a category no longer recognized as a product but as a descriptor of the two. The only proof I found of its existence as a brand long ago are old advertisements from between the 1930s and 1940s.

Source: Special Collection & Archives, UC San Diego Library

Also, in the graveyard of brands is the Band-aid. People started using the brand to refer to all sticky plasters, but to be fair, the brand did try to fix this mass misunderstanding. In its American advertisements there was a song that used to be “I am stuck on Band-Aid, ’cause Band-Aid’s stuck on me”, but when the brand was getting blurry to the public in the 1980s it was changed to “I am stuck on Band-Aid Brand, ’cause Band-Aid’s stuck on me”. Maybe the brand would have survived if only this clarification was made sooner (Marsden, 2011).

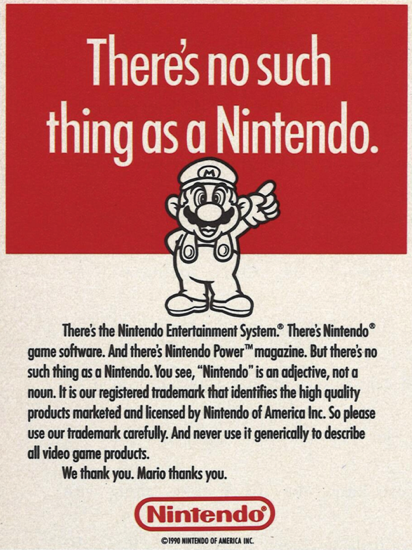

Here are brands that are not dead but got paranoid and took a more blunt approach to their marketing. The gaming brand Nintendo produced the ad below to discourage its consumers from calling its video game products by the brand name itself (Marsden, 2011).

Kleenex too has its issues, as people started using it to mean any facial tissues. Consumers probably don’t even realize it, but if this habit continues, Kleenex will get wiped. Adamant on protecting the brand name, the company sends letters to whoever wrongfully uses it (Duffy, 2003).

In 2005, Google aware and wary of its popularity, released a “rules for proper usage” for its brand. A list of do’s and don’ts, such as to capitalize the G and never use it as a verb. Still, in 2006 Google entered Merriam-webster dictionary, now this is bad, but it could have been worse. Because it was not defined in a broad sense but limited the action to obtaining information using the Google search engine specifically. Earlier this year there has been a lawsuit against the brand. It was aiming to cancel the trademark on the basis that it has become a verb. However, there was no way of determining that the consumers didn’t have Google search engine in mind when they say ‘Googled it’. Because of that, Google won the lawsuit (Justia US Law, 2017). What also helped Google in court was the relentless actions it took against misuse of their brand. Which shows that the brand was never careless about its name and so shouldn’t be held accountable for this misuse.

Coke is not so chill when it comes to protecting its brand from genericide. The brand has filed a suit against a local restaurant in the U.S. for underhandedly replacing customers’ orders for coke with a non-coke beverage. The restaurant defense is that Coke has become a generic name to all cola beverages. The court noted that despite the fact that the customer used the brand in a generic sense saying “a coke”, no one can prove if they had Coke in mind and not any other brand. Based on that, the court was in favor of the Coca-Cola Company (Justia US Law, 2017). Now you might think: “but this is no big deal, it’s a win against a small time restaurant”, but what took place was marketing. Doing this, the brand managed to hit two targets in one go. It’s setting an example to all not to misuse their brand and its spreading awareness of the problem.

Brands can spread awareness and protect their brand in a smart way instead of telling people to knock it off. The previous examples of blunt brands, can come across as being bossy instead of clear. However, we can only see how effective that is in years to come. I think brands should be less blunt and more creative. The band-aid ad was the best in my opinion, but I think that in their case, it was a matter of bad timing. They were clear in their distinction and they did it in a fun creative way, the only fault is that it was too late. Genericide can be avoided by careful and consistent marketing. Highlighting the distinction not only from competing brands but from the category itself.

References:

- https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/genericide

- Tulett, Simon. “’Genericide’: Brands Destroyed by Their Own Success.” BBC News, BBC, 28 May 2014, www.bbc.com/news/business-27026704.

- Elliott v. Google, Inc., No. 15-15809 (9th Cir. 2017) http://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/ca9/15-15809/15-15809-2017-05-16.html

- Peterson, Becky. “This 1979 Letter to The New York Times Shows Just How Much Xerox Hates People Using Its Name as a Verb.” Business Insider, Business Insider, 27 July 2017, www.businessinsider.com/old-letter-to-new-york-times-xerox-takes-trademark-very-seriously-2017-7.

- Marsden, Rhodri. “’Genericide’: When Brands Get Too Big.” The Independent, Independent Digital News and Media, 9 June 2011, www.independent.co.uk/news/business/analysis-and-features/genericide-when-brands-get-too-big-2295428.html.

- Duffy, Jonathan. “Google Calls in the ‘Language Police’.” BBC News, BBC, 20 June 2003, news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/3006486.stm.

amazing post i like it